Chapter 7

Fundamentals of Options Trading

Imagine walking into a room filled with tools. At first, they all look unfamiliar — levers, pulleys, dials — each one promising power, but only if you understand how to use it. That’s what options trading is like for most people at the beginning: strange, complex, and just a little dangerous.

But there’s a reason those tools are there.

At some point, every trader reaches a limit with stocks alone. Maybe it’s the capital requirement. Maybe it’s the desire to amplify a small edge. Or maybe it’s simply the realization that you don’t always need to buy 100 shares to bet on a move — sometimes, one well-placed option is enough.

In the 2008 crash, some investors lost everything. Others made fortunes — not because they were smarter, but because they understood how to control risk while using leverage. They didn’t gamble. They used options deliberately, like a mechanic choosing the right tool for the job.

This chapter isn’t about turning you into a professional options trader. It’s not about complex spreads, Greek formulas, or income strategies. Instead, it’s about giving you just enough power to do something useful — and to do it safely.

We’ll focus on call options, and how they can be used to gain leveraged exposure to SPY — the same ETF we’ve been building toward throughout this book. You’ll learn how options really work, why they cost what they do, how they can expire worthless, and what makes them such a powerful part of a modern trader’s toolkit.

Later, we’ll backtest SPY call strategies across decades of data. But first, we need to understand the mechanics — not just how options move, but why they behave the way they do.

If you’ve ever looked at an options chain and thought, "This looks complicated", you’re not alone. But by the end of this chapter, it won’t be.

Let’s open the toolbox and get to work.

7.1 Why trade options? A preview of power and risk

Options exist for one reason: to give traders more flexibility.

With stocks, your choices are simple — you either buy, sell, or hold. But options offer a broader set of tools: you can hedge a portfolio, generate income, or make directional bets with significantly less capital than buying the stock itself.

Let’s briefly look at the three primary reasons traders use options:

- Leverage: Gain exposure to a stock’s movement without tying up the full cost of buying shares. A small move in the stock can translate into a much larger percentage move in the option’s value.

- Hedging: Use options to protect an existing position from downside risk. This is often compared to buying insurance.

- Income: Generate steady cash flow by selling options, often in strategies like covered calls or cash-secured puts.

All of these are valid uses — but in this book, we’ll focus on the first: using call options for directional leverage on SPY.

The goal is to participate in bullish moves while putting less capital at risk than if you bought SPY shares directly. In many cases, a single call option contract can control 100 shares — allowing you to magnify gains, but also increasing your exposure to loss if you’re wrong.

This isn’t about gambling. It’s about using the tool of leverage with purpose, backed by understanding and discipline. And, most importantly, it’s about testing whether this approach has worked in the past — using real data, across decades of SPY price history.

But before we can evaluate performance, we need to understand how options actually work — and why they behave differently from stocks.

7.2 Understanding call and put options

At its core, an option is a contract. It gives the buyer the right — but not the obligation — to buy or sell an underlying asset at a specified price, on or before a certain date.

Strike Price and Premium Paid

Every option contract has two key numbers you must understand:

- Strike Price: The price at which you have the right to buy (for a call option) or sell (for a put option) the underlying stock. Example: If you own a call option with a $100 strike price, you can buy the stock at $100, no matter what its current market price is.

- Premium Paid: The upfront cost to purchase the option. Example: If the premium is $5, you must pay $5 per share (typically $500 per contract, since each option controls 100 shares).

The premium is the price you pay for the possibility of future profits. If the stock price moves favorably, you can make much more than the premium you paid. If not, the maximum loss is limited to the premium itself.

Call Options

A call option gives the buyer the right to buy a stock at a specific price, known as the strike price, before the option expires.

Think of it like a reservation. If you have a call option on SPY with a strike price of $400, you have the right to buy SPY at $400 — even if the current market price rises to $420. That difference — the gap between the current price and the strike — can turn into profit.

Each option contract typically controls 100 shares. So if the option is worth $5, that means it would cost you $500 to buy one contract ($5 x 100).

Call options increase in value when the stock price goes up. That makes them useful for traders who want to bet on upside movement, without putting up the full cost of buying shares. This is where the power of leverage comes into play.

Put Options (for context)

A put option gives the buyer the right to sell the underlying stock at the strike price before expiration. Puts increase in value when the stock price goes down, and they’re commonly used as insurance or to speculate on bearish moves.

While puts are an important part of the options world, we won’t focus on them in this book. Our interest lies in how call options can be used to create leveraged strategies with defined risk — particularly in the context of SPY.

| Aspect | Call Option | Put Option |

| Right to... | Buy the stock | Sell the stock |

| Bullish or Bearish? | Bullish (betting on price going up) | Bearish (betting on price going down) |

| Profit when... | Stock price rises above strike + premium | Stock price falls below strike - premium |

| Maximum loss | Limited to premium paid | Limited to premium paid |

| Maximum profit | Unlimited | Limited (stock can’t go below zero) |

| Used for... | Leveraged upside potential | Downside protection or bearish speculation |

Options Are Rights, Not Obligations

It’s important to remember: buying an option gives you the right to act, not the obligation. If the market doesn’t move in your favor, you can simply let the option expire. Your maximum loss is the premium you paid — no more.

In the next section, we’ll break down how that premium is determined — and what it really means when traders talk about intrinsic value and time value.

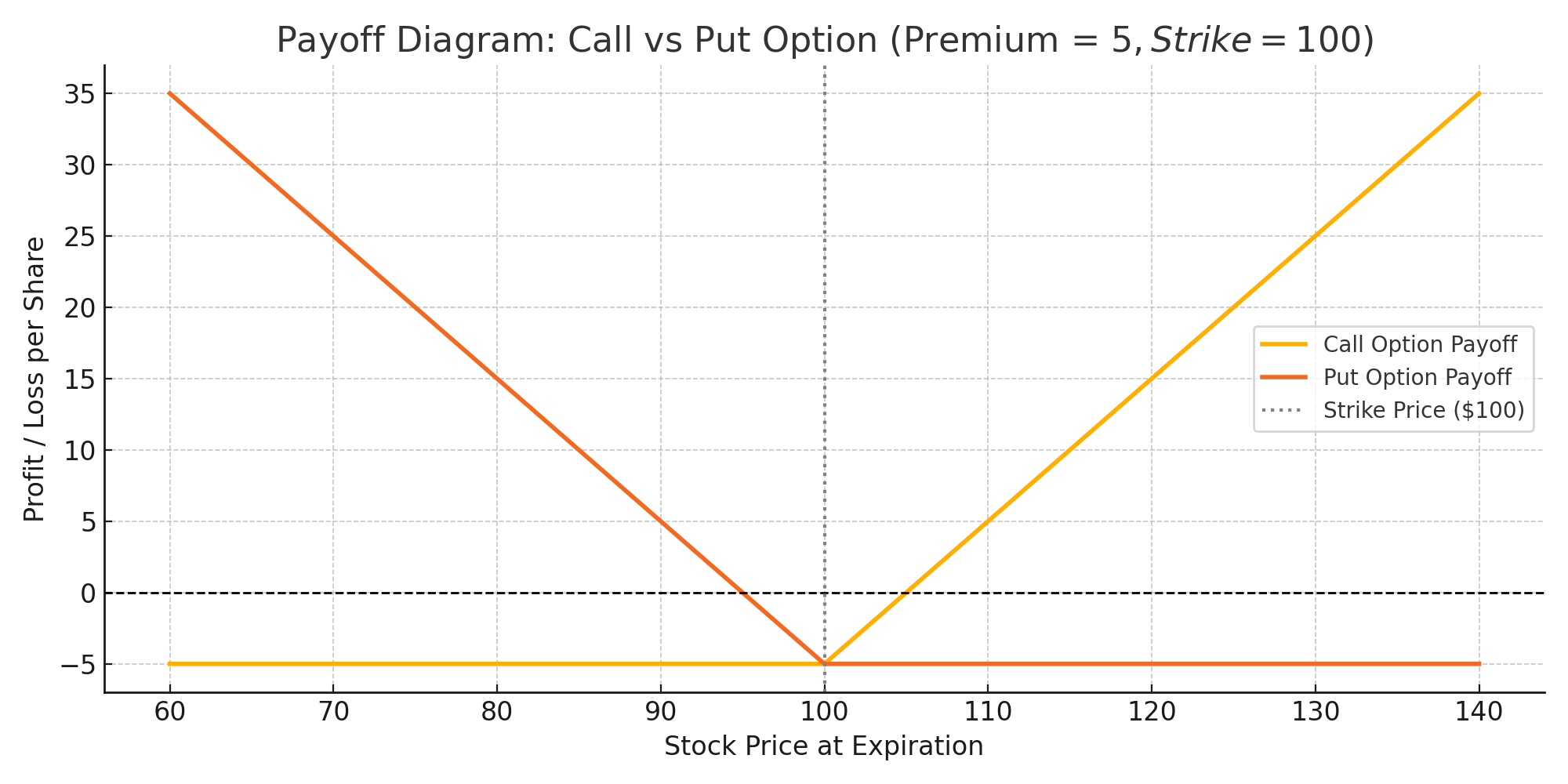

Understanding an Option Payoff Diagram

This diagram shows the payoffs for a call and a put option with:

- Strike price: $100

- Premium paid: $5

All examples below assume the stock price at expiration.

-

If stock price is $90 (below strike price):

- Call option expires worthless. Loss = premium paid = $5.

- Put option finishes in the money. Profit = $100 - $90 - $5 = $5.

-

If stock price is $100 (at strike price):

- Both call and put options expire worthless. Loss = premium paid = $5.

-

If stock price is $110 (above strike price):

- Call option finishes in the money. Profit = $110 - $100 - $5 = $5.

- Put option expires worthless. Loss = premium paid = $5.

Breakeven points:

- For the call option: stock price = $105

- For the put option: stock price = $95

In both cases, the maximum loss is limited to the premium paid ($5), while potential gains are theoretically unlimited (for calls) or substantial (for puts).

7.3 Intrinsic value and time value explained

When you buy an option, the price you pay is called the premium. But where does that number come from?

Option premiums are made up of two components: intrinsic value and time value. Understanding the difference is key to knowing what you’re really paying for — and what you’re risking.

Intrinsic Value

Intrinsic value is the amount by which an option is "in the money" (ITM).

For a call option, it’s the difference between the current stock price and the strike price — but only if the stock price is higher than the strike.

For example, if SPY is trading at $410 and you own a call with a $400 strike price, the intrinsic value is $10.

If the option is not in the money (e.g., SPY is at $390 and your call strike is $400), then the intrinsic value is zero.

Time Value

Time value is the portion of the premium that reflects the possibility of future gains. It accounts for the chance that the option could become profitable before expiration.

Even if an option is out of the money (OTM), it still has time value — especially if there’s a lot of time left before expiration or high market volatility.

Time value decreases as the expiration date gets closer — a phenomenon known as theta decay. The closer you get to expiration, the faster this decay happens. This is why options are considered "wasting assets" — their value erodes over time if the underlying stock doesn’t move.

ITM, ATM, and OTM Explained

Options are often categorized based on their relationship to the current stock price:

- In the Money (ITM): A call option where the stock price is above the strike price.

- At the Money (ATM): A call option where the stock price is very close to the strike.

- Out of the Money (OTM): A call option where the stock price is below the strike price.

Generally, ITM options are more expensive because they already have intrinsic value. OTM options are cheaper but rely entirely on time value — meaning they need the stock to move in your favor before expiration to have any value at all.

Why This Matters

When you buy a call option, you’re not just betting that the stock will rise — you’re betting it will rise enough to cover both the strike price and the premium. Understanding intrinsic and time value helps you avoid overpaying for low-probability bets.

In the next section, we’ll walk through how to actually buy a call option — and how to read an options chain so you can see these values in action.

7.4 Getting started with options trading

Now that you understand what options are and how they’re priced, let’s walk through how to actually place a trade.

In this section, we’ll explore how to use an options chain, how to choose a strike price and expiration date, and how to buy a basic call option — step by step.

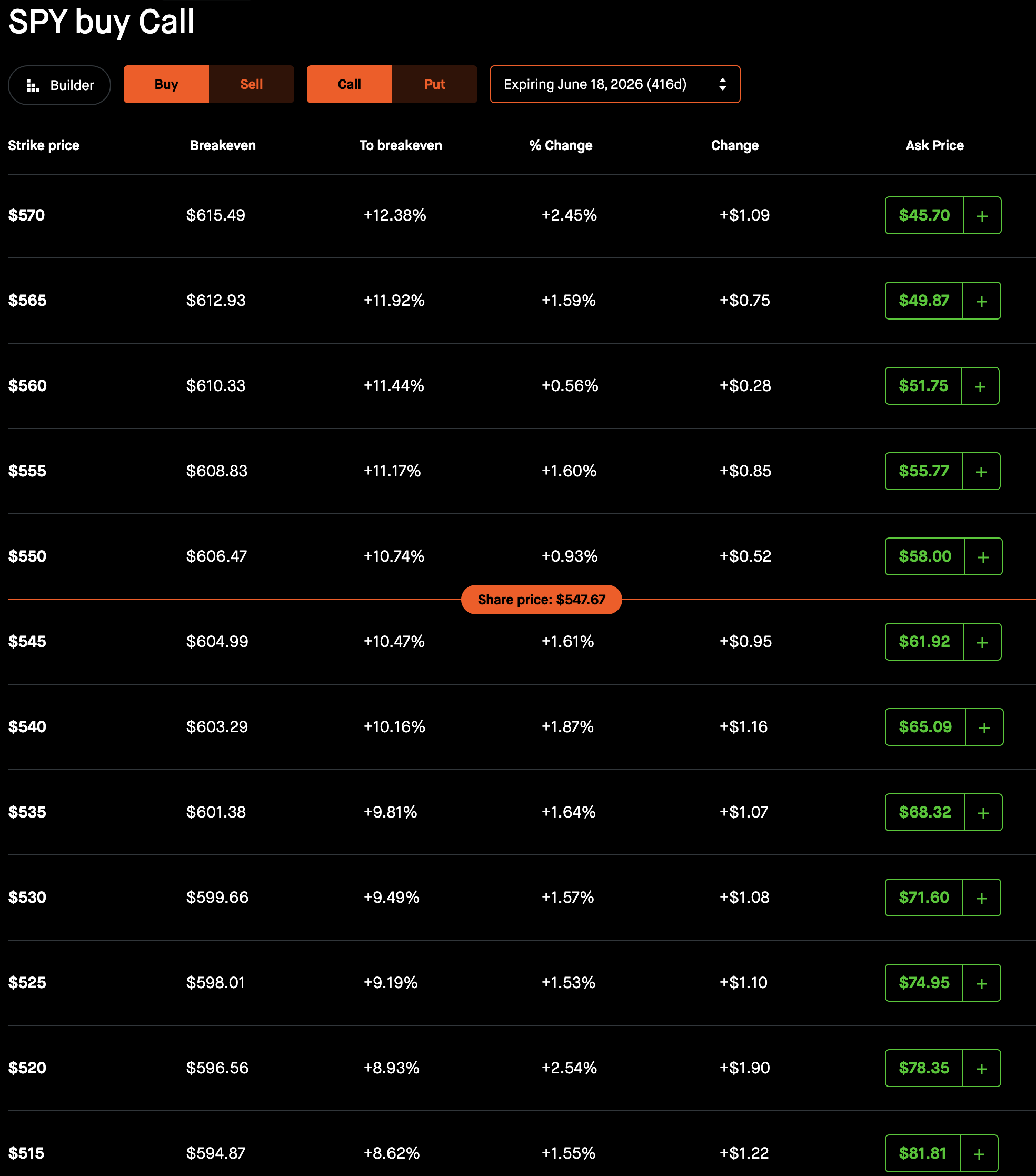

Understanding the Call Option Chain

The table above shows a call option chain for SPY, expiring on June 18, 2026 (416 days from today). We focus only on buying call options — not selling options or buying puts.

Here are the key columns explained:

- Strike Price: This is the agreed price at which you have the right to buy SPY shares before expiration. For example, a strike price of $550 means you can buy SPY for $550, no matter what its actual market price is.

- Breakeven: This is the stock price you would need at expiration to recover the cost of buying the call. It equals Strike Price + Premium Paid. Example: For the $550 strike, breakeven is $606.47.

- To Breakeven (%): How much SPY would need to rise (in percentage terms) from today’s price to reach your breakeven point.

- % Change: The percentage change in the option’s price compared to the previous trading day.

- Change ($): The dollar amount that the option’s price has increased or decreased today.

- Ask Price: The current price you must pay per share to buy the option. Since each contract controls 100 shares, multiply this price by 100 to calculate the full cost. For example, the ask price for the $550 call is $58.00, so the total cost is about $5,800.

At the center of the table, you will also see the current share price for SPY — in this case, $547.67. It is highlighted to help you quickly see which options are near the money (close to the current price).

Summary:

- Options with a strike below $547.67 are in the money (ITM).

- Options with a strike above $547.67 are out of the money (OTM).

When buying calls, you usually choose a strike price depending on your view:

- Lower strikes (ITM) are more expensive but safer.

- Higher strikes (OTM) are cheaper but riskier.

Choosing the right call option involves balancing cost, breakeven, and your expectations for how much SPY might rise.

Choosing the Right Call Option

When you buy a call, you’re speculating that the stock price will rise. But how far, and how soon?

Here are the two main factors you must choose:

- Expiration date: The date the option contract expires. More time gives you more flexibility but costs more.

- Strike price: The price at which you have the right to buy the stock. Lower strikes are more expensive but more likely to be profitable.

Example: Buying a Deep In-the-Money SPY Call Option

Suppose SPY is currently trading at $550.

You decide to buy a call option with the following details:

- Strike price: $350

- Premium paid: $210

- Expiration: 1 year from today

Note: Option premiums are quoted per share, but each contract controls 100 shares. Thus, buying one contract would cost $210 × 100 = $21,000.

Understanding the Outcome

At expiration, all time value disappears — the option’s worth is purely based on intrinsic value:

-

If SPY rises to $750:

- Intrinsic value = $750 - $350 = $400 per share

- Total value = $400 × 100 = $40,000

- Profit = $40,000 - $21,000 = $19,000

- Percentage return =

-

If SPY falls to $450:

- Intrinsic value = $450 - $350 = $100 per share

- Total value = $100 × 100 = $10,000

- Loss = $21,000 - $10,000 = $11,000

- Percentage loss =

This example shows:

- Deep ITM calls behave similarly to owning SPY shares, but with leveraged gains and losses.

- Even though the option is far in the money, you can still lose money if SPY does not rise enough.

- Your maximum loss is always limited to the premium paid (in this case, $21,000).

Summary

Buying a call option is a simple way to gain leveraged exposure to an upside move — with limited downside. But success depends on choosing the right strike, expiration, and risk amount. In the next section, we’ll look at what you need to do before you can place these trades: enable options permissions with your broker.

7.5 Broker permissions: enabling options on Robinhood

Before you can place your first options trade, most brokers — including Robinhood — require you to apply for options trading permissions. This isn’t a bug in the system — it’s by design.

Why Do Brokers Restrict Options Trading?

Options are powerful tools. They carry risks that most beginner investors are not familiar with, such as:

- Losing 100% of your investment if the option expires worthless

- Misunderstanding time decay (theta) or leverage

- Accidentally trading strategies that involve unlimited risk (such as selling naked calls)

To protect both you and themselves, brokers require users to pass a short application process to verify basic knowledge and financial suitability.

Understanding Permission Levels

Brokers categorize options access into different levels. Robinhood, for example, typically uses:

- Level 1: Covered calls (basic income strategies)

- Level 2: Buying calls and puts (our focus)

- Level 3+: Advanced multi-leg strategies (e.g., spreads, iron condors)

To follow the strategies in this book, you only need Level 2: the ability to buy call options.

How to Enable Options Trading on Robinhood

Here’s how to apply for options trading in the Robinhood app:

- Open the Robinhood app and tap the account icon in the bottom right.

- Tap "Settings", then tap "Investing".

- Look for "Options Trading" and tap it.

-

You’ll be prompted to answer a few questions about your:

- Trading experience

- Financial background (income, net worth)

- Risk tolerance

- Submit the form. Approval is usually instant, but may take up to 1 business day.

If you’re not approved immediately, don’t worry. You can retake the quiz later, and you can still practice reading options chains in the meantime.

Other Brokers

Most major brokers — such as Fidelity, E*TRADE, Tastytrade, and Schwab — follow a similar process. While interfaces differ, the basic principle is the same: request access, demonstrate understanding, and start small.

What Comes Next

Once your account is approved for options trading, you’re ready to place your first call option trade. In the coming chapters, we’ll gradually shift from theory to testing — using real SPY data to measure how well different call strategies have worked in the past.